UMKC researchers are using 21st century scientific methods to follow a paper trail across medieval Europe.

The interdisciplinary project by principal investigators Virginia Blanton, Ph.D., professor of English and department co-chair; Reza Derakhshani, Ph.D., associate professor of computer science and electrical engineering; Nathan Oyler, Ph.D., associate professor of chemistry; and Jeff Rydberg-Cox, director of classics and ancient studies, is a collaboration at the nexus of science and humanities.

“No one investigator could do this project,” Blanton says. “It takes a web of talents and knowledge among disciplines to complete.”

The researchers are using multispectral analysis to help uncover the history of medieval books, with a goal of developing a center to encourage interdisciplinary collaboration on the topic. The center would serve as a training ground for graduate students, a venue for undergraduate research and a base for faculty research, Rydberg-Cox says. It also would be an incubator for licensable technologies that would allow small libraries to analyze works in their own collections.

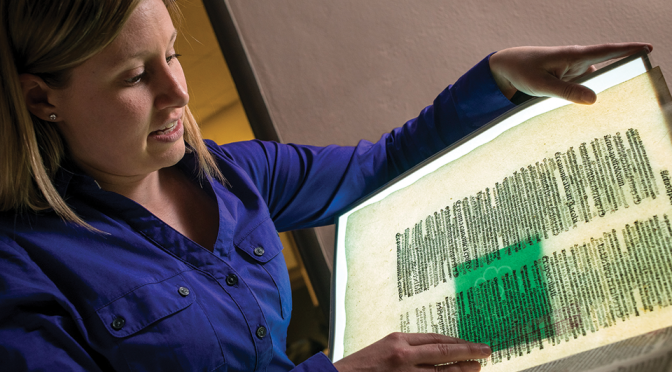

The researchers have designed and built an apparatus that captures images at wavelengths along the electromagnetic spectrum. Those images provide information about early books invisible to the naked eye. For example, multispectral imaging can reveal the ghostly lettering of text previously scraped or erased and then overwritten in different ink. It can distinguish the pages that were touched — and used — most often. And it can detect the unique chain-and-laid-line pattern created by each papermaker’s mold.

Additionally, chemical analysis differentiates the quality of inks and pigments used in a book, offering clues to the intended audience. Researchers glean other information by studying books’ bindings, fonts and watermarks.

“If we can isolate chain-and-laid lines alongside a watermark, and thus identify a particular mold for a given sheet of paper, we can work to match it against other paper used in other books, which would tell us something about the use of paper across all printing,” Blanton says. “Watermarks can help us locate a given paper maker, identify a region of production and isolate trade routes for paper.”

When pieced together, the researchers’ findings will provide important insights into the economic, political, religious and societal happenings of medieval Europe.

The UMKC team has been busy analyzing a 1486-87 edition of Summa theologica, written in the mid-1400s by the archbishop of Florence to guide priests in instructing parishioners. The printed volumes — owned by Conception Abbey in northwest Missouri — have taken up temporary residence in a tiny lab in Cockefair Hall on Volker campus, where researchers have taken visible-light photographs of every page. An extensive history of the book’s physical attributes has been written, and multispectral images are being made of select pages.

Machines that perform this kind of spectroscopy are expensive and exceed the budgets of most small libraries, Rydberg-Cox says. So the UMKC researchers have built their own spectrometer from cameras, filters and lenses scavenged across campus. Eventually they hope to post do-it-yourself instructions for their spectrometer online, as well as tutorials on how to conduct multispectral imaging of medieval manuscripts and books printed within 100 years of the invention of the printing press (1450). The goal is to make the process so affordable and understandable that even small libraries and student researchers can participate and contribute.

“Really, we are more focused on the process of discovery and less focused on the results,” Blanton says.

In the second phase of their research, which began in August 2014, the UMKC team is studying a 16th-century Gregorian chant book held in the LaBudde Special Collections at UMKC’s Miller Nichols Library. The researchers already know that some chants were scraped off and rewritten. Others were adapted to be performed by female instead of male cantors — information of special interest to musicologists and monastic historians.

The team, with collaborators from the University of Missouri in Columbia, will also turn its attention to a liturgical text, produced in Eastern Europe about 1500, that belongs to Special Collections and Rare Books in Ellis Library at MU.

Since its launch two years ago, the research project has received $250,000 funding from three sources: the Digital Humanities Start-Up Grant program of the National Endowment for the Humanities, the University of Missouri Research Board and the University of Missouri System Interdisciplinary Intercampus Research Grant Program. The team is seeking additional funding for what promises to be a long-term project.

Following the paper trail that leads from medieval printers in Europe to modern libraries throughout Missouri is a multifaceted task that will catalyze interdisciplinary study across UMKC for years to come.