Inside the UMKC School of Biological Sciences, you’d expect to find classrooms, labs, offices and study spaces.

What you might not expect to find is a room filled, floor-to-ceiling, with fish tanks.

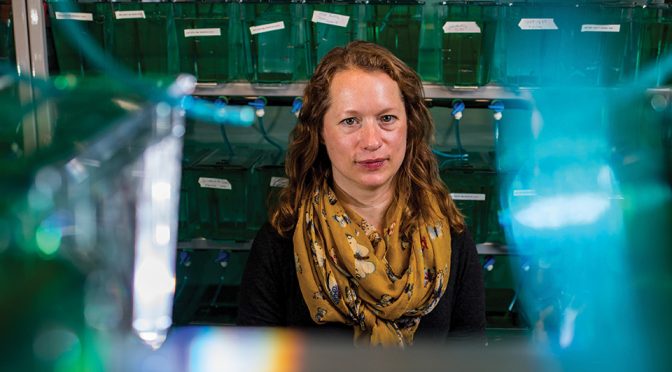

The space resembles something like a high-tech pet store, without all the colored rocks and miniature castles. It’s kept at a balmy 82 degrees, and a complex filtering system runs through each tank, keeping the water clean and at the right salinity.

It’s all part of the research being conducted by Hillary McGraw, Ph.D., an assistant professor of cell biology and biophysics. She’s spent most of her academic career studying the zebra fish and what their development can teach us about human development.

Despite the obvious differences in size, habitat and biology, zebra fish and humans share some of the same developmental processes. McGraw says there is a lot to be learned about humans by studying these tiny organisms.

“The really amazing thing about zebra fish is that they are fertilized and develop outside of the mother,” she says. “So we can watch really early processes in formation because they’re just in water and not inside another organism.”

Another great thing about zebra fish is that they’re essentially transparent, meaning researchers can observe their cell movements in real time.

McGraw pulls out a laptop and shows a video of a two-day-old zebra fish embryo. Its cells have been biologically engineered to emit a glowing, green color, so she can observe how they move through the body.

“We can see a lot of things happening that you couldn’t see in other animals,” McGraw says. “Being able to take live video of the processes I’m studying is such a powerful tool.”

When you picture cancer research, you may think of patients in a hospital, receiving a new treatment or taking part in the study of a new medication. Those kinds of studies, however, take place near the end of the research process.

McGraw and her zebra fish are, as she puts it, at the “starting point of cancer research.”

Many cancers begin at the very earliest stages of human life – within a developing embryo. The cancer will take a certain process that was used in the developing embryo and reactivate it in the adult, which helps it to invade cells throughout the body.

McGraw hopes her work will help inform what goes wrong during cancer cell movements, and how to stop cancer in its earliest stages.

“When you have just a tumor, a tumor can be removed. But once the cancer cells start to move throughout the body, that’s when things really go wrong,” she says. “So if we can figure out how to stop that, I think that is one of the critical points in cancer biology.”

McGraw’s work could also help treat hearing impairment in humans. Zebra fish — like many types of fish — have a sensory system that allows them to sense changes in water currents.

The cells that make up the sensory system in zebra fish are very similar to hair cells within the human ear – with one very important difference.

“These cells in our ears – they don’t grow back, which is why we go deaf. When they’re damaged, they’re just gone,” McGraw says. “But in fish, these cells are actually able to grow back.”

Understanding how fish are able to regrow their sensory cells could help researchers understand how to regrow the cells in human ears after hearing loss has occurred.

Inside her brand-new lab space, McGraw pulls out a petri dish and places it under a microscope. In the dish are several zebra fish that she estimates to be three — no, four — days old.

“They’re very small. You can kind of see them swimming around in there,” she says. “At this stage they have nice big eyes, and they’re starting to hunt for food.”

As she peers carefully into the microscope, the obvious question arises: Do you have fish at home? She laughs.

“I actually don’t. It’s so much easier to have this controlled environment here. And I have a cat, so those don’t mix very well.”

After less than a year at UMKC, McGraw’s research is still in its preliminary stages. She hopes, however, that her work will help form some of the questions researchers are asking many years from now.

“Every time you answer one problem, it kind of opens up the next question,” she says. “That’s what I really like about science, is that it’s constantly evolving and progressing.”